Since the U.S. presidential election and the Brexit referendum, both in 2016, the risk to Western democracies from fake news has been part of the global political debate. But in the twenty-first century, five years of technology is a long time. And the dangers have grown, becoming more sophisticated. While platforms and the authorities barely manage to lessen the spread of fake news on platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp, new risks are starting to be tangible within the development of Artificial Intelligence (AI). In 2021, we should no longer trust a video with inflammatory statements from a political leader: it might have been created with AI. And these deep fakes are just one of the manifestations of the phenomenon we find ourselves in.

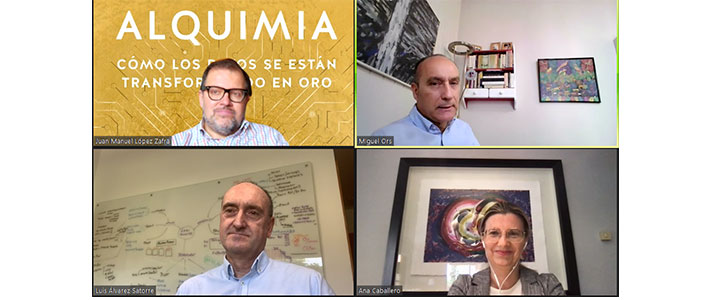

All these manipulations, and the hate speech they often engender, quickly catch fire on social media, contrary to the firewalls they come up against in the media. The press, even with their inaccuracies, errors, and biases, are a basic pillar to protect democratic systems against all those who, from political or corporate power, can use technology to undermine them. This was the subject of the recent roundtable, ‘Too big to fail: Can large platforms compromise the security, economic system, and democratic quality of our countries?’, organized by the newspaper El Mundo and its economic supplement, Actualidad Económica. Participants included Ana Caballero, Vice President of the European Association for Digital Transition (EADT), Luis Álvarez Satorre, CEO of the cybersecurity company SIA, and Juan Manuel López Zafra, economist and data expert, especially in its use in the financial world.

The risk of citizens’ data being used for political or electoral purposes has an aspect of cybersecurity, but as the moderator of the conference, journalist Miguel Ors, said in his introduction, “The great danger lies with those who have legal access to your data”. At one extreme is the Chinese regime, which has no qualms about establishing its mechanisms for social control through technology. In the West, democratic systems impose a different framework, respectful of individual rights. But the advance of technology and the power of the large platforms has caused cracks in this system.

The EU is reacting to this situation with two basic regulations, the Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act. Caballero, as the EADT spokesperson, offered congratulations on these developments, as “there is no freedom without order, and there is no order without regulation”.

As opposed to the voices accusing Europe of curbing technological innovation with rules and requirements, Caballero defended the European model, whose regulations, in areas such as the protection of personal data, are a global model. “The large platforms see Europe as a mere source of data”, she explained, “and it’s very difficult to get them out of this context. They don’t want regulation because they live very comfortably. But we need rules that put the European citizen at the centre and ensure balanced business competition”.

However, not everything is regulation. López Zafra stressed the need to educate citizens “to be aware of the value of data, and not only monetarily, but also the value of usage”. Álvarez Satorre, from SIA, called for more awareness from each of us. “With fake news there is clear individual responsibility”, he said, and explained it with a very graphic example: “Imagine an apartment building with many neighbours giving information about the building and the neighbourhood. Some are reliable, others aren’t. It’s our responsibility to distinguish between them”.

López Zafra expressed real concern about the evolution of liberal democracies: “We are moving toward a controlled democracy, one in which the feeling of freedom matters more than freedom itself,” he said. “States, in concert with technological platforms, tend to increasingly invade individual freedoms”. The brake on this drifting depends in part on the role of the media, which must be “empowered”, said Caballero: “They make mistakes and perpetrate excesses, but are essential”.

The media can be heroes and also villains if, backed-up by technology, they shape public opinion spuriously. It is not a question of establishing any kind of prior censorship on the media, something all the speakers agreed on. But rather to reflect and take action facing the risk posed by the combination of enormous technological power in very few hands and the ability of that technology to alter our democratic processes, which depend on the truthful transmission of information. “Whoever controls the technology, controls everything”, Caballero summed up. And that is a risk to our political freedoms.